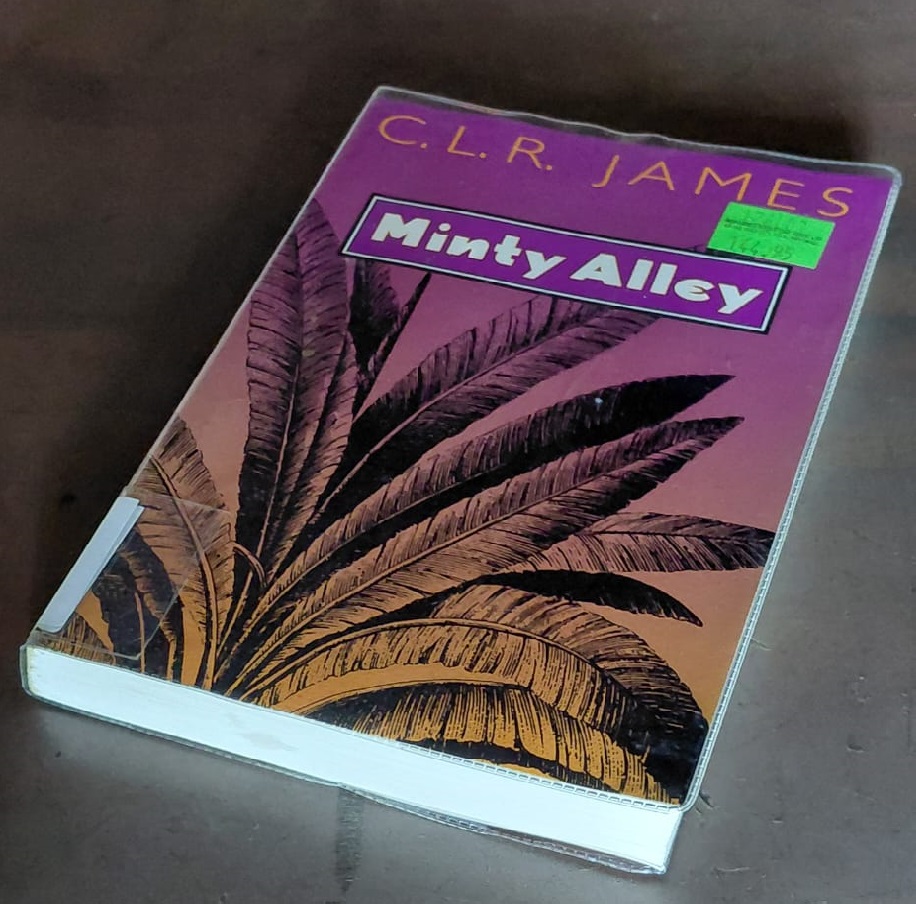

Minty Alley

Started reading this in December when I found out that an alternative ending had been found by a researcher. Dr. Kaneesha Parsard was working in the CLR James archives at the UWI, St. Augustine Library when she discovered it.

As she writes in her paper, James was a well-known Marxist philosopher and social activist. He felt a rewrite of the ending of his already published novel was necessary. And as his widow Selma mentioned in conversation with the British Library a few years back, he was using fiction to play with his writing and political thought. To work out his concerns with class in the Caribbean context, the complex relationship between the lower and middle classes. Their awareness of each others realities, saying that he knew, as soon as his education blinded him to their humanity he was no longer capable of true activism.

Borrowed from NALIS, Port of Spain

I related to Minty Alley deeply. The way we are taught, via our still very colonial education system to disconnect with my blackness. That I was fortunate to have gone to a secondary school that pushed back on that conditioning. That I had friends who through direct education and shared experiences opened my mind and my willingness to remove the scales from my eyes. That I studied sociology in at a Caribbean university; developing an ability to see Trinidad society critically.

I also loved the language and was intrigued by that way he spelled it. That has changed, but it reads so easily. It is not a heavy novel, and is a quick light read, that could easily be completed in a day, or two.

His sharing of the lives of these flawed but well-meaning (for the most part) characters made for an enjoyable read. I loved the treatment of Maisie, who as a singular type of young women often is made to pay for her outspokenness and confidence for us to see. That does not happen, and I was grateful. There is ambiguity in her prospects that allow for the reader to imagine a realistic positive, or negative outcome.

Mr. Haynes is a typical naive middle-class mama’s boy. Who is surrounded by women who will coddle, protect and defer to him purely because his is a man, but young enough for them to protect, even while they recognise the authority he holds by virtue of being a man. He does not turn into a dog at the end of the novel, a choice I was also grateful for, but he does grow in his eventful year at #2 Minty Alley.

James is able make the petty dramas we engage in seem weighty in its superficiality. Sometimes we are knowingly engaging in nonsense, yet we persist. That is on full display here, the conflict is all interpersonal and could be resolved with self-restraint and open conversation. But such is life.

And as a West Indian it leaves you with a better understanding of how this deliberate inability to see each other fully manifests in our political decisions and the unequal societies, we have created for ourselves.